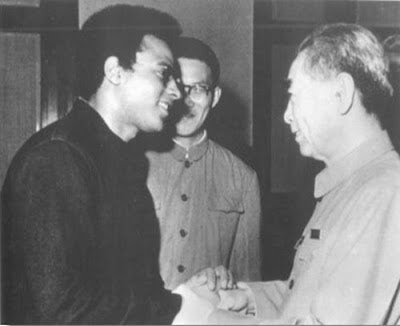

Huey Newton meeting Chinese Premier - Chou En Lai

The 1946 Chinese revolution ensured the independence of China from once being a semi-colony of many european colonialists. The revolution also developed in a socialist direction. The Chinese revolution was one of the most important revolutions of the last century, which inspired a new wave of revolutionary struggles for several decades.

The African Revolution and the Black Liberation Movement was also inspired by the Chinese revolutionaries, and Mao's statement on the Black Liberation struggle, arising from discussions with pioneering black revolutionary Robert F Williams, helped to put Mao and the Chinese revolution as a champion of the Black Revolution.

Sukant Chandan, Sons of Malcolm

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

China

Chapter 32

From Revolutionary Suicide

The people who have triumphed in their own revolution should help those still struggling for liberation. This is our internationalist duty.

(Mao Tse-tung, Little Red Book)

Today, when I think of my experiences in the People’s Republic of China – a country that overwhelmed me while I was there – they seem somehow distant and remote. Time erodes the immediacy of the trip; the memory begins to recede. But that is a common aftermath of travel, and not too alarming. What is important is the effect that China and its society had on me, and that impression is unforgettable. While there, I achieved a psychological liberation I had never experienced before. It was not simply that I felt at home in China; the reaction was deeper than that. What I experienced was the sensation of freedom as if a great weight had been lifted from my soul and I was able to be myself, without defense or pretense or the need for explanation. I felt absolutely free for the first time in my life completely free among my fellow men. This experience of freedom had a profound effect on me, because it confirmed my belief that an oppressed people can be liberated if their leaders persevere in raising their consciousness and in struggling relentlessly against the oppressor.

Because my trip was so brief and made under great pressure, there were many places I was unable to visit and many experiences I had to forgo. Yet there were lessons to be learned from even the most ordinary and commonplace encounters: a question asked by a worker, the response of a schoolchild, the attitude of a government official. These slight and seemingly unimportant moments were enlightening, and they taught me much. For instance, the behaviour of the police in China was a revelation to me. They are there to protect and help the people, not to oppress them. Their courtesy was genuine; no division or suspicion exists between them and the citizens. This impressed me so much that when I returned to the United States and was met by the Tactical Squad at the San Francisco airport(they had been called out because nearly a thousand people came to the airport to welcome us back), it was brought home to me all over again that the police in our country are an occupying, repressive force. I pointed this out to a customs officer in San Francisco, a Black man who was armed, explaining to him that I felt intimidated seeing all the guns around. I had just left a country, I told him, where the army and the police are not in opposition to the people but are their servants.

I received the invitation to visit China shortly after my release from the Penal Colony, in August, 1970. The Chinese were interested in the Party’s Marxist analysis and wanted to discuss it with us as well as show us the concrete application of theory in their society. I was eager to go and applied for a passport in late 1970, which was finally approved a few months later. However, 1 did not make the trip at that time because of Bobby’s and Ericka’s trial in New Haven. Nonetheless, I wanted to see China very much, and when I learned that President Nixon was going to visit the People’s Republic in February, 1972, I decided to beat him to it. My wish was to deliver a message to the government of the People’s Republic and the Communist Party, which would be delivered to Nixon when he made his visit.

I made the trip in late September, 1971, between my second and third trials, going without announcement or publicity because I was under an indictment. I had only ten days to spend in China. Even though I had no travel restrictions and had been given a passport, the California courts could have tied me down at any time because I was under court bail, so 1 avoided the states jurisdiction by going to New York instead of directly to Canada from California. Because of my uncertainty about what the power structure might do. I continued to avoid publicity after reaching New York, since it was not implausible that the authorities might place a federal hold on me, claiming illegal flight. By flying from New York to Canada I was able to avoid federal jurisdiction, and once in Canada I caught a plane to Tokyo. Police agents knew of my intentions, and they followed me all the way right to the Chinese border. Two comrades, Elaine Brown and Robert Bay, went with me. I have no doubt that we were allowed to go only because the police believed we were not coming back. If they had known I intended to return, they probably would have done everything possible to prevent the trip. The Chinese government understood this, and while I was in China, they offered me political asylum, but I told them I had to return, that my struggle is in the United States of America.

Going through the immigration and customs services of the imperialist nations was the same dehumanizing experience we had come to expect as part of our daily life in the United States. In Canada, Tokyo, and Hong Kong they took everything out of our bags and searched them completely. In Tokyo and Hong Kong we were even subjected to a skin search. I thought I had left that routine behind in the California Penal Colony, but I know that the penitentiary is only one kind of captivity within the larger prison of a racist society. When we arrived at the free territory, where security is supposed to be so tight and every-one suspect, the comrades with the red stars on their hats asked us for our passports. Seeing they were in order, they simply bowed and asked us if the luggage was ours. When we said yes, they replied, “You have just passed customs.” They did not open our bags when we arrived or when we left.

As we crossed into China the border guards held their automatic rifles in the air as a signal of welcome and well-wishing. The Chinese truly live by the slogan “Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun,” and their behavior constantly reminds you of that. For the first time I did not feel threatened by a uniformed person with a weapon; the soldiers were there to protect the citizenry.

The Chinese were disappointed that we had only ten days to spend with them and wanted us to stay longer, but I had to be back for the start of my third trial. Still, much was accomplished in that short time, traveling to various parts of the country, visiting factories, schools,and communes. Everywhere we went,large groups of people greeted us with applause, and we applauded them in return. It was beautiful. At every airport thousands of people. welcomed us, applauding, waving their Little Red Books, and carrying signs that read WE SUPPORT THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY, DOWN WITH U.S. IMPERIALISM, OR WE SUPPORT THE AMERICAN PEOPLE BUT THE NIXON IMPERIALIST REGIME MUST BE OVERTHROWN.

We also visited as many embassies as possible. Sightseeing took second place to Black Panther business and our desire to talk with revolutionary brothers, so the Chinese arranged for us to meet the ambassadors of various countries. The North Korean Ambassador gave us a sumptuous dinner and showed films of his country. We also met the Ambassador from Tanzania, a fine comrade, as well as delegations from North Vietnam and the Provisional Revolutionary Government of South Vietnam. We missed the Cuban and Albanian embassies be-cause we were short of time.

When news of our trip reached the rest of the world, widespread attention focused on it, and the press was constantly after us to find out why we had come. They were wondering if we sought to spoil Nixon’s visit since we were so strongly opposed to his reactionary regime. Much of the time we were harassed by reporters. One evening a Canadian reporter would not leave my table despite my asking him several times. He insisted on hanging around, questioning us, even though we had made it plain we had nothing to say to him. I finally became disgusted with his persistence and ordered him to leave. Seconds later, the Chinese comrades arrived with the police and asked if I wanted him arrested. I said no, I only wanted him to leave my table. After that we stayed in a protected villa with a Red Army honor guard outside. This was another strange sensation- to have the police on our side.

We had been promised an opportunity to meet Chairman Mao, but the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party felt this would not be appropriate since I was not a head of state. But we did have two meetings with Premier Chou En-lai. One of them lasted two hours and included a number of other foreign visitors; the other was a six-hour private meeting with Premier Chou and Comrade Chiang Ching, the wife of Chairman Mao. We discussed world affairs, oppressed people in general, and Black people in particular.

On National Day, October 1, we at-tended a large reception in the Great Hall of the People with Premier Chou En-lai and comrades from Mozambique, North Korea, North Vietnam, and the Provisional Government of South Vietnam. Normally, Chairman Mao’s appearance is the crowning event of the most important Chinese celebration, but this year the Chairman did not put in an appearance. When we entered the hall, a band was playing the Internationale, and we shared tables with the head of Peking University, the head of the North Korean Army, and Comrade Chiang Ching, Mao’s wife. We felt it was a great privilege.

Everything I saw in China demonstrated that the People’s Republic is a free and liberated territory with a socialist government. The way is open for people to gain their freedom and determine their own destiny. It was an amazing experience to see in practice a revolution that is going forward at such a rapid rate. To see a classless society in operation is unforgettable. Here, Marx’s dictum- from each according to his abilities, to each according to his needs- is in operation.

But I did not go to China just to admire. I went to learn and also to criticize, since no society is perfect. There was little, however, to find fault with. The Chinese insist that you find something to criticize. They believe strongly in the most searching self-examination, in criticism of others and, in turn, of self. As they say, without criticism the hinges on the door begin to squeak. It is very difficult to pay them compliments. Criticize us, they would say, because we are a backward country, and I always replied, “No, you are an underdeveloped country.” I did have one criticism to make during a visit to a steel factory. This factory had thick black smoke pouring into the air. I told the Chinese that in the United States there is pollution because factories are spoiling the air; in some places the people can hardly breathe. If the Chinese continue to develop their industry rapidly, I said, and without awareness of the consequences, they will also make the air unfit to breathe. I talked with the factory workers, saying that man is nature but also in contradiction to nature, because contradictions are the ruling principle of the universe. Therefore, although they were trying to raise their levels of living, they might also negate the progress if they failed to handle that contradiction in a rational way. I explained that man opposes nature, but man is also the internal contradiction in nature. Therefore,while he is trying to reverse the struggle of opposites based upon unity, he might also eliminate himself. They understood this and said they are seeking ways to remedy this problem.

My experiences in China reinforced my understanding of the revolutionary process and my belief in the necessity of making a concrete analysis of concrete conditions. The Chinese speak with great pride about their history and their revolution and mention often the invincible thoughts of Chairman Mao Tse-tung. But they also tell you, “This was our revolution based upon a concrete analysis of concrete conditions, and we cannot direct you, only give you the principles. It is up to you to make the correct creative application.” It was a strange yet exhilarating experience to have traveled thousands of miles, across continents, to hear their words. For this is what Bobby Seale and I had concluded in our own discussions five years earlier in Oakland, as we explored ways to survive the abuses of the capitalist system in the Black communities of America. Theory was not enough, we had said. We knew we had to act to bring about change. Without fully realizing it then, we were following Mao’s belief that “if you want to know the theory and methods of revolution, you must take part in revolution. All genuine knowledge originates in direct experience.”