REPORT: Police Killings In San Francisco Bay Area

Law Enforcement Related Deaths in the US: “Justifiable Homicides” and the Impacts on Families

September 10, 2014By Peter Phillips, Diana Grant and Greg Sewell

Editors note: The full version of this study with all of the citations will be published in Censored 2015: Inspiring We the People, edited by Andy Lee Roth, Mickey Huff, and Project Censored, Seven Stories Press, official release date October 7, 2014.

According to newspaper accounts over 1,500 people die annually in the US in law enforcement related deaths. These are all deaths in the presence of law enforcement personnel both on the street and in local jails. Infamous cases such as Andy Lopez, Oscar Grant, and Michael Brown are only the tip of the iceberg. Many hundreds more are killed annually and these deaths by police are almost always ruled justifiable, even when victims are unarmed or shot in the back running away.

We interviewed 14 families who lost loved ones in law enforcement related deaths in the SF Bay Area from 2000-2010. All the families believe their loved one should not have been killed and most felt that the police over-reacted and murdered their family member. All families reported abuse by police after the deaths. Most also reported that the corporate media was biased in favor of the police and failed to accurately report the real circumstances of the death.

Beginning in 1996 activists in New York organized a national protest day on October 22 each year. The October 22nd Coalition to Stop Police Brutality, Repression and the Criminalization of a Generation says that they “bring forward a united, powerful, visual coalition of families victimized by police terrorism.”

In 1998 Project Censored co-sponsored a research study with the Stolen Lives Project a group born out of the October 22nd Coalition. Through funding from the San Francisco Foundation, Karen Saari, a legal researcher in Sonoma County California, spent a good part of a year searching the newspaper databases Lexis-Nexis and Proquest online at Sonoma State University for articles on Law Enforcement Related Deaths. She was searching for police shootings and any situation reported in the newspapers where someone died in the presence of law enforcement officers. Besides gun shots, deaths included suicides, car accidents, shootings, drowning, and Taser use.

To our knowledge, this was the first time such a study had been attempted in the U.S. During the twelve-month period October 1, 1997 to October 1, 1998, Saari found news stories on 694 deaths in the presence of law enforcement that occurred in the United States. Department of Justice figures at the time listed about 350 people killed by police in the previous year, so Saari’s research showed a significantly higher rate of death among civilians in law enforcement incidents than was previously known at the time.

In 2011, Jim Fisher used Internet searches to identify 1,146 police shootings that year. Of this number news reports indicated that 607 people died. This was a slightly higher rate of shooting deaths than had been reported in 1997-98, but did not include taser, restraint deaths and suicides. Fisher found that vast majorities of the people shot were between the ages of 25-49, a result similar to Saari’s report a decade earlier. In 2011 two victims of the police were 15 years of age and one girl was only 16. Fifty of the dead were armed with BB-guns, pellet guns or toy replica firearms.

In addition to the people dying on the street or in their homes through law enforcement related activities, research shows that several hundred people a year die in local jails. In 2011, according to the Office of Justice Programs, 885 inmates died in the custody of local jails. Thirty-nine percent died within the first week of being jailed. This number combined with deaths on the outside shows that in excess of 1,500 people die annually in law enforcement related circumstances both in custody or in the process of enforcement in the community. It is reasonable to assume that some portion of these deaths is attributable to officer mistakes, over- reactions, or deliberate acts resulting in death.

But almost always, despite obvious questionable behavior by law enforcement personnel, no charges are filed. Police investigations of law enforcement related death, either internally within departments or by outside police agencies, nearly always rule homicides are justifiable and followed departmental procedures. It is extremely rare for police departments to rule a death as unjustified or to charge an officer with neglect, manslaughter, or murder.

Research has shown that it was a much graver error for a street cop to use too little force and begin developing a reputation among fellow officers as a shaky officer than to engage in excessive force and be told by colleagues to calm down. When officers do not use enough force they are subject to reprimand, gossip, and avoidance in the police subculture. The dangers associated with the occupation often prompt officers to distance themselves from the chief source of danger — citizens. The coercive authority that officers possess also separates them from the public. The cultural prescriptions of suspiciousness and maintaining the edge over citizens in creating, displaying, and maintaining their authority further divides police and people in the community. Officers who are socially isolated from citizens, and who rely on one another for mutual support from a dangerous and hostile work environment, are said to develop a “we versus they” attitude toward citizens and strong norms of loyalty to fellow officers.

We believe that certain behavior changes by police could well result in the lowering of law enforcement related deaths in the U.S. We decided to interview families of people who died in a law enforcement related incident. Our research team interviewed fourteen individuals who were immediate family members of people who died in Law Enforcement related incidents in northern California between 2000 and 2010. At least one year had passed from when their loved one died and the date of the interview. Interviews were recorded and transcribed for analysis and comparison. All the names of the interviewees and the victims are to remain anonymous to protect the privacy of the families.

Following is a brief outline of the key facts as reported by family members for the fourteen cases and their opinions on the death. In all fourteen cases, the investigating police departments ruled the deaths justifiable homicide. In case # 9 a narcotics officer was indicted by the Grand Jury, but was found innocent in a court trial. All the family members interviewed strongly believe that police overreacted and their loved one should not have been killed under the circumstances.

Case #1. White male, Age 29, San Anselmo, prior history of mental illness, in-home traumatic episode, victim charges police with small steak knife, shot to death.

Interviewee #1, “I think he (police officer) acted hastily…the cop that did it shouldn’t have a gun…he is the problem.”

Case #2. Black male, Age 19, High School Senior, Hayward, shot in back of head while running away from Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) police, no record of mental illness, no weapons present,

Interviewee #2, “The police and the media just said …the officer felt threatened by my son and had to shoot him. Very few newspapers changed their story or apologized when they found out my son was shot in the back of the head.”

Case #3. Black Male, Age 30, Rohnert Park, prior drug use, shot in back running from police after car chase, no record of mental illness, no weapons present,

Interviewee #3, “he was running from the police…they shot him in the back…murdered by the police.”

Case #4. Black Male, Age 27, Oakland, prior drug use and sales, no history of mental illness, shot in back running from police, threw away handgun before being shot, financial settlement to family from civil trial.

Interviewee #4, “He had to run because he had a pistol on him. The police chased him. He ran around the corner and threw away the gun. The cop saw him throw away the gun and I guess decided it was ok to go ahead and shoot. He was shot two or three times in the back.”

Case #5. Black male, Age 23, San Francisco, bipolar and depressed, confrontation in movie theater over smoking, shot 48 times by nine officers, no weapons, financial settlement to family from civil trial.

Interviewee #5, “They (police) evacuated all the theater… and they got in and shot him 48 times. They (Cops) posted stuff on my son’s website. I checked the IP address and it came form the police station, (they wrote) “who cares about your dead baboon on welfare?”

Case #6. Black male, Age 73, Ukiah, long history of mental illness, local psych unit asked police to pick him up so he could take his medications, runs to his apartment chased by police dog, dog attacks him and he responds with sharp object, shot several times in back and side by police.

Interviewee #6, “In my opinion he was murdered.”

Case #7. Black male, Age 30, Rohnert Park, self-employed rapper, prior arrests for marijuana and passing counterfeit money, no recorded mental illness, ran from police after traffic stop, shot in back, no weapons present.

Interviewee # 7, “He ran (from the car after a stop) and was shot immediately in the back. And then he was dead. He and the officer that shot him …had gone to school together and played basketball together.”

Case #8. White male, Age 39, Petaluma, prior depression and minor drug use, not taking his medications, traumatic episode called 911 himself, rampaging in his parents home, tasered by police three times and dies, no weapons present.

Interviewee #8. “The police…are supposed to protect you and take care of you, and we were following the rules.”

Case #9. Latino male, Age 40, San Jose, prior felon, no history of mental illness, mistaken identity car chase by under-cover narcotics officers, runs from car and shot in back by officer, bleeds to death after delayed medical care, no weapons present, financial settlement to family after civil suit.

Interviewee #9, “My uncle happens to drive by a stakeout and he fits the description of a Mexican guy with a mustache…in a blue van. The undercover narcotic officers gave chase,… my uncle didn’t know who they were…he ends up on a one-way street and stops his car, and starts to run away. My uncle jumps a fence and the officer shoots him in the middle of the back. They let him lay there for eleven minutes bleeding…finally they let the ambulance in and he dies on the way to the hospital.”

Case #10. Black male, Age 16, 127 lbs, Sebastopol, no prior criminal record, depressed, traumatic episode in van parked in family driveway with small carving knife, pepper sprayed and shot six times by county sheriff, financial settlement to family from civil trial.

Interviewee #10, “The officer was highly reactive and he didn’t assess the situation, he immediately jumped into plan of action and that escalated the situation rather then contain it. Both officers said they feared for their life, yet these officers were both more than twice the weight of my 127 lb son.”

Case #11. Latino male, Age 34, San Jose, prior drug use, no history of mental illness, single officer confrontation 3:00 AM in front of his children’s and ex-partner’s home, tasered by officer, physical struggle, shot four times, no weapons present.

Interviewee # 11, “his autopsy report showed that he had been hit four times with bullets through his left side. He was unarmed. The police said they are trained to stop a threat. And I said well my god if this officer felt threatened what about a shot to the leg or something…and he responded no we are trained to show center space in the body. You know if you can’t shoot center space you won’t be a police officer.”

Case #12. White male, Age 24, Santa Rosa, mentally ill ward of the state, schizophrenic, in and out of care facilities since age 14, stopped taking medication and had psychotic incident in his home shard by three men, picked up small kitchen knife and is tasered and then shot by police four times, small financial settlement from civil suit.

Interviewee #12, “There are probably a great many combat veterans in the police…you have been taught to kill, They could have stepped back The first thing they could have done is not make him come out of his room. Anyone who knows anything about mental patients who are off their meds—just get them somewhere quiet and alone.”

Case #13, White-Korean male, Age 30, Santa Rosa, Mental Illness Bipolar and PTSD, fired gun afraid of intruders in his attic, taken by police outside, runs at officers shot, no weapon in possession at time of shooting.

Interviewee # 13, “They kept shouting orders at him, I believe there were six officers, they approached in formation all of them with their guns aimed at him and to someone in this mental state it was extremely threatening way to approach him. (They had him on the ground) and kept shouting confusing orders to him, turn your head to the right, turn your head to the left, then he jumped up…and they shot him a rifle in the chest, right in the heart. None of this would have happen, all they had to do was say we are here to help, we understand you are hearing intruders, do you mind if we take a look?”

Case #14. Black male double amputee in wheelchair, Age 61 and his son, age 21, Oakland, Police arrive seeking proof of vaccination for dog that was reported to have bit someone in the home, , father killed with one shot to heart, son killed with 13 shots, officer dies (family says from friendly fire), police claim son had a shotgun, mother says no gun in the house, tape recording hidden by police for six years shows cooperative son, and no shotgun blast.

Interviewee #14, “I think the reason officers do what they do is because they can. It is just like any human reaction that if there are not consequences, then you have a green light….they don’t pay lawsuits, the taxpayers do, they seldom get fired for wrongdoing. So basically what they do is with impunity be they know the odds of any negative impact coming back to them …is negligible.”

Most all of the families complained that the police lied to them after the death of their family member and the media backed up the police. In most cases, immediate family members are isolated from each other, and taken to the police station. Families were kept from knowing that their loved one was dead. Questioning by police was designed to build a negative case against the deceased.

Certainly, the sudden death of a loved one is a very traumatic event for anyone. However, adding in isolation, interrogations, and lies will undoubtedly magnify the trauma. These families carry a deep-seated anger towards the police, not only for killing their loved ones but also for what they see as gross mistreatment by authorities after the event. Not only do they understand that after a law enforcement related death police immediately circle the wagons and go into protective mode, but they also see the media as likely to accept press releases from the police unquestioningly and conduct little in the way of investigative reporting.

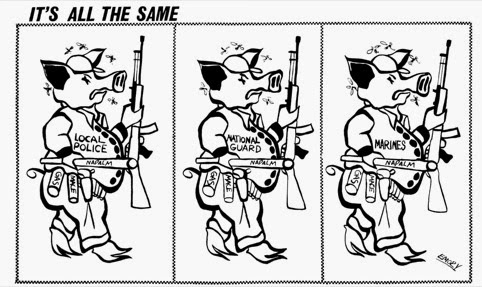

In conclusion, we believe that, with some 1,500 people dying annually, a major continuing problem with law enforcement related death exists in the US. The national move to militarized police with homeland security oversight is certainly not reducing this death rate. Long-term racism continues to show abuses affecting people of color to greater degrees that whites. The culture of policing tends to reward aggressive behavior and diminish efforts to mitigate shooting deaths. And families of law enforcement related death victims are mistreated and abused by police departments and the corporate media.

We think that a comprehensive review of police training is needed to give greater emphasis to the use of non-lethal interventions, and non-aggressive behaviors especially in mental health cases. Mental health/social service support for families of victims of law enforcement related deaths, given the testimony above, is an important social justice need for people already suffering serious trauma.

______________________________________________________________________

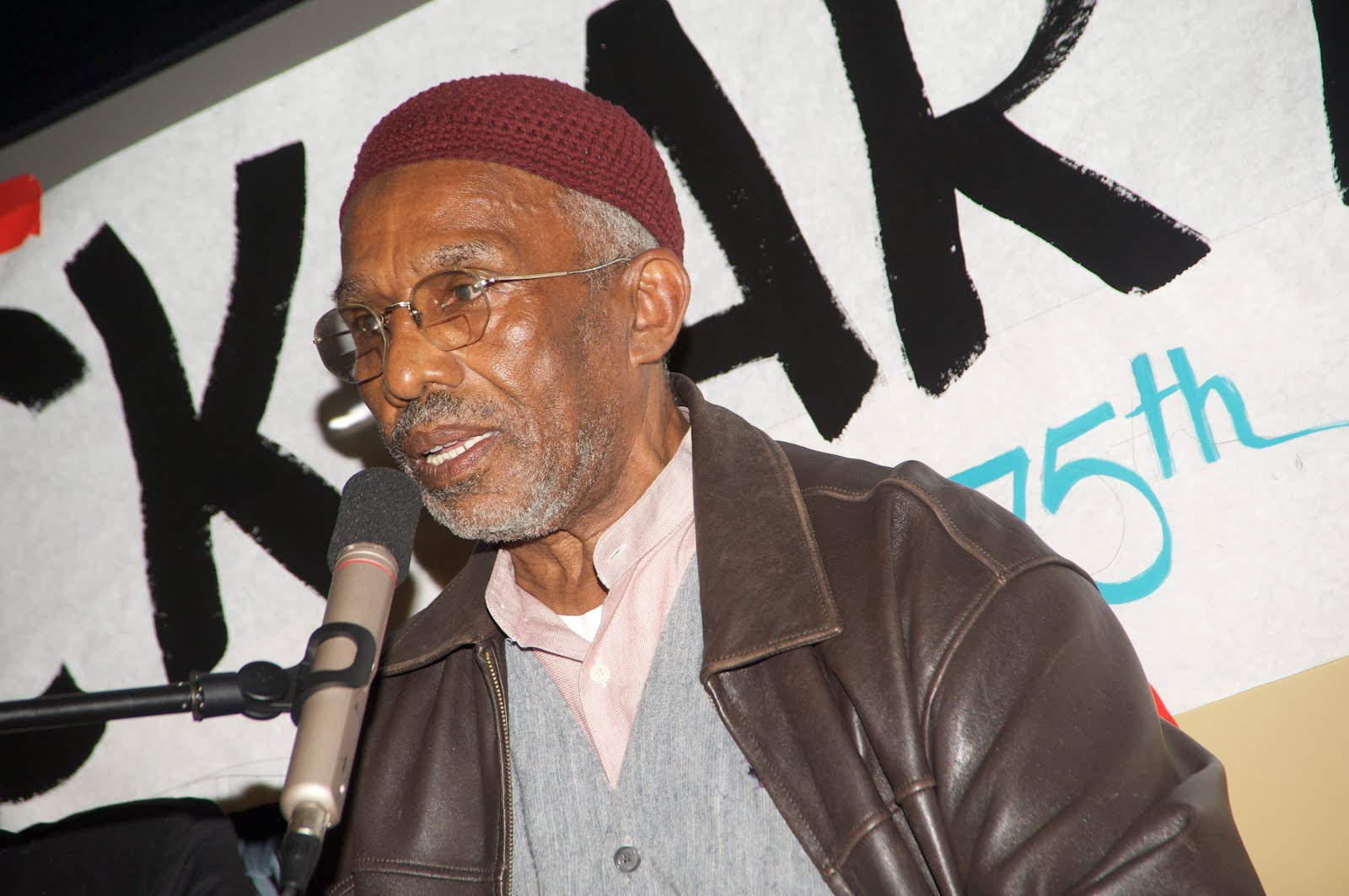

• Peter Phillips is a Professor of Sociology at Sonoma State University, and President of Media Freedom Foundation/Project Censored

• Diana Grant is a Professor of Criminology & Criminal Justice Studies at Sonoma State University

• Greg Sewell is a recent sociology graduate from Sonoma State University

Posted 10th September by black left unity network

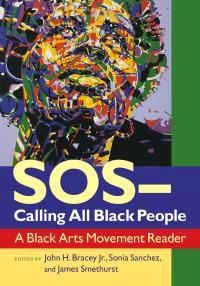

A major new anthology of readings, this volume brings together a broad range of key writings from the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and 1970s, among the most significant cultural movements in American history. The aesthetic counterpart of the Black Power movement, it burst onto the scene in the form of artists’ circles, writers’ workshops, drama groups, dance troupes, new publishing ventures, bookstores, and cultural centers and had a presence in practically every community and college campus with an appreciable African American population. Black Arts activists extended its reach even further through magazines such as Ebony and Jet, on television shows such as Soul! and Like It Is, and on radio programs. Many of the movement’s leading artists, including Ed Bullins, Nikki Giovanni, Woodie King, Haki Madhubuti, Sonia Sanchez, Askia Touré,Marvin X and Val Gray Ward, remain artistically productive today. Its influence can also be seen in the work of later artists, from the writers Toni Morrison, John Edgar Wideman, and August Wilson to actors Avery Brooks, Danny Glover, and Samuel L. Jackson, to hip-hop artists Mos Def, Talib Kweli, and Chuck D. SOS—Calling All Black People includes works of fiction, poetry, and drama in addition to critical writings on issues of politics, aesthetics, and gender. It covers topics ranging from the legacy of Malcolm X and the impact of John Coltrane’s jazz to the tenets of the Black Panther Party and the music of Motown. The editors have provided a substantial introduction outlining the nature, history, and legacy of the Black Arts Movement as well as the principles by which the anthology was assembled.

A major new anthology of readings, this volume brings together a broad range of key writings from the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and 1970s, among the most significant cultural movements in American history. The aesthetic counterpart of the Black Power movement, it burst onto the scene in the form of artists’ circles, writers’ workshops, drama groups, dance troupes, new publishing ventures, bookstores, and cultural centers and had a presence in practically every community and college campus with an appreciable African American population. Black Arts activists extended its reach even further through magazines such as Ebony and Jet, on television shows such as Soul! and Like It Is, and on radio programs. Many of the movement’s leading artists, including Ed Bullins, Nikki Giovanni, Woodie King, Haki Madhubuti, Sonia Sanchez, Askia Touré,Marvin X and Val Gray Ward, remain artistically productive today. Its influence can also be seen in the work of later artists, from the writers Toni Morrison, John Edgar Wideman, and August Wilson to actors Avery Brooks, Danny Glover, and Samuel L. Jackson, to hip-hop artists Mos Def, Talib Kweli, and Chuck D. SOS—Calling All Black People includes works of fiction, poetry, and drama in addition to critical writings on issues of politics, aesthetics, and gender. It covers topics ranging from the legacy of Malcolm X and the impact of John Coltrane’s jazz to the tenets of the Black Panther Party and the music of Motown. The editors have provided a substantial introduction outlining the nature, history, and legacy of the Black Arts Movement as well as the principles by which the anthology was assembled.